By Mara Schanfield - March 11, 2022

This blog serves as a summary of the October 13, 2021 National Center Roundtable event.

Social and emotional learning (SEL) and trauma-informed practices (TIP) (also known as trauma-sensitive schools (TSS)) promote relationships, safety (physical, emotional, and identity), and self-regulation. On their own, these approaches can build individual skills. Both approaches can enhance educators’ capacity to respond to students (and each other) and to troubling situations in helpful ways, whether or not individuals have experienced adversity. When intertwined, SEL and TIP can transform structures and systems to foster healing, empowerment, and culturally-affirming conditions that support well-being for all1.

Deliberately integrating SEL and TIP can prevent:

- fragmentation (working in silos)

- duplication (expending valuable resource like time and educator bandwidth)

- conflation (confusion or incomplete understanding)

Let’s take some time to consider how to deliberately integrate these school-wide supports in this summary of a recent event on this very topic.

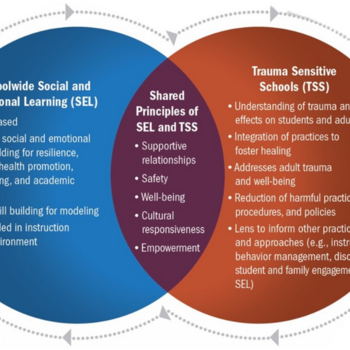

On October 13, 2021, the National Comprehensive Center and Region 9 Comprehensive Center co-hosted a virtual roundtable session on how to integrate SEL and TIP. The event featured Dr. David Osher from the American Institutes for Research (air.org). He described the shared principles of SEL and TIP/TSS (Figure 1) and discussed how they strengthen social, emotional and academic development. Osher emphasized that structural inequities can limit opportunities for people to grow and develop their social and emotional competencies which are some of the very skills that help us to cope with trauma. Operating from the shared principles of SEL and TIP/TSS can help school and district leaders maximize opportunities for healing-centered engagement.

Figure 1. Shared principles

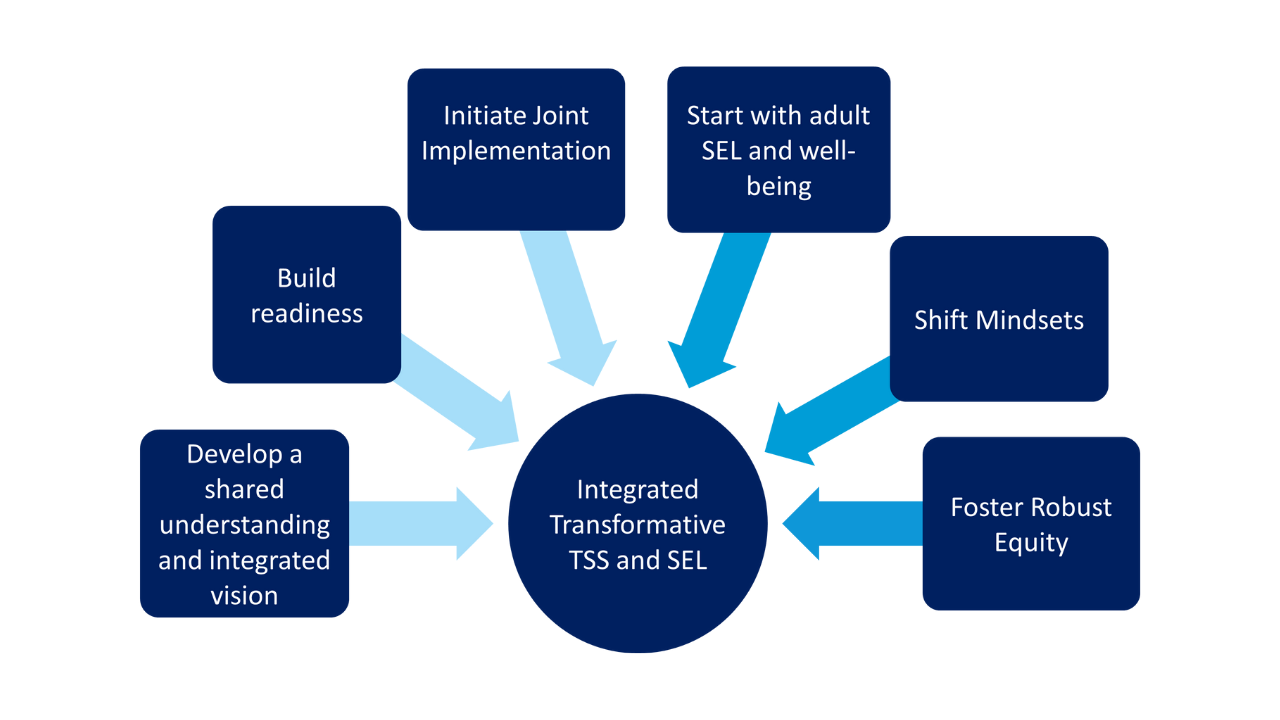

Osher offered six key strategies for integrating SEL and TIP in an equity-centered and culturally affirming manner, featured in figure 2.

Figure 2. Key Strategies for Integrating and Expanding Trauma Sensitive Schools and SEL

The first three strategies on the left in light blue (i.e. develop a shared understanding and integrated vision, build readiness, and initiate joint implementation) come from standard and effective implementation practice of any effort. Standard practice means operating within an existing system (including systems with baked-in structural racism) and is likely to maintain the status quo. SEL and TIP, when integrated, can change not only practice but the system itself. The three strategies on the right in bright blue (i.e. support adult SEL and well-being, shift mindsets, and foster robust equity) help systems transform by centering equity. Osher’s message was clear, “…without changing the systems and structures that are producing inequitable outcomes, we won’t reduce disparities.” It is this systems-level change that moves us toward justice.

Three Districts’ Journeys

Following Osher’s keynote, presenters from three districts (Fulton County Schools, Georgia; Juneau School District, Alaska; and Metro Nashville Public Schools, Tennessee) shared their implementation journeys connecting and applying SEL and TIP strategies. The three featured districts had committed to SEL and TIP well before 2020, but the additional circumstances brought on by COVID-19 elevated the importance of their work. They offered examples of what district support can look like to make a real difference for students, families and educators by:

-

Teaching student success skills and preparing for success beyond the classroom (Fulton County Schools)

-

Supporting school counselors to process secondary trauma (Juneau School District)

-

Addressing root causes of discipline disparities for Black and Brown students (Metro Nashville Public Schools).

Here are some additional details about these examples from the district panel:

Fulton County School System, Georgia

Chelsea Montgomery, executive director, Office of Student Supports

“To implement effectively], you don’t need a massive number of people—you just need solid structures.” – Chelsea Montgomery, Fulton County Schools

Fulton County’s journey began with the deliberate solicitation of SEL vendors to meet student needs. They considered fit, feasibility, and usability (using National Implementation Research Network’s hexagon tool) and selected Rethink Ed. They brought stakeholders together to articulate a vision for Fulton County’s “student success skills” that are now being taught by teachers and assessed districtwide twice a year. Faced with implementation challenges during a pandemic, Fulton County Schools required teachers to use only four SEL lessons in fall 2020, and gave school administrators the option to delay rollout of the remaining lessons until January 2021. District leaders were delighted to find that this opt-in approach resulted in higher-than-expected use -- nearly 80% of schools continued the SEL lessons rather than delaying; indicating the program appeared to be addressing a real-time need. By providing options to school leaders, the district models a key principle of trauma sensitivity upfront (“choice and voice” is a pillar of trauma-informed approaches4).

Although proactive, universal prevention approaches (known within a Multi-Tiered System of Supports5 as Tier 1) can help narrow the pipeline of students needing more intensive supports, Fulton County took a different approach. The district’s approach differed because of the urgent and widespread needs it had identified. So many students had such intensive needs that the district chose to address targeted and intensive supports for Tiers 2 and 3 immediately, then strengthen Tier 1 over time. Recognizing a need for more human resources, the district team got creative. They designed a support role for social workers who could case-manage students (1:1 support) while formally coaching teachers on student success skills. Putting the structures and systems in place to support the social workers helped maximize impact of tiered supports.

Juneau School District, Alaska

Ted Wilson, director, Teaching and Learning Support & Maressa Jensen, coordinator, Trauma Engaged Practices

“It’s important to have safe spaces [for educators] to process how things are going.” - Maressa Jensen, Juneau School District

In Juneau School District, leadership started by conducting an inventory of current SEL and TIP efforts and resources to understand what already was taking place across the district. The results of the inventory showed full-time counselors at every elementary school, teen health centers in every high school, and an SEL program in the middle schools. With an understanding of what existed, district leadership redirected resources where possible based on need. Unable to address all needs with current resources, they went after large grants which provided the means to enhance and extend their vision for trauma-engaged schools. By taking an asset-based approach, the district models a key principle related to SEL and trauma sensitivity6. The timing of implementation coincided with a statewide initiative for trauma-engaged schools7, which led to positive public attention and resources for the district. Partners and grant funding then made it possible to elaborate on existing practice so the district pursued a three-pronged strategy. First, it partnered with the Collaborative Learning for Educational Achievement and Resilience (CLEAR) program by piloting at three Title I elementary schools. Second, the district hired more support staff (a district coordinator, part-time student and family advocates, district family engagement and trauma-informed schools specialists, and mental health clinicians for middle and high schools). Third, the new district staff coordinated and offered ongoing training aimed at building school capacity targeting support staff.

One of the district’s most successful training efforts, “Reflective Practice,” consisted of monthly virtual 2-hour sessions for school counselors with an outside consultant. This effort provided time, space, and guidance for support staff to process their own experiences (including secondary trauma) and experience a trauma-engaged way of being among peers, which has been well-attended by counselors. One indication of value is the time being held sacred – counselors prioritize attending and principals make sure no other meetings encroach on this time. By offering a safe, supportive, and healing space to counselors themselves, the district models a key principle related to SEL and trauma sensitivity.

Metro Nashville Public Schools, Nashville, Tennessee

Mary Crnobori, coordinator of trauma-informed practices, Department of Student Support Services

Metro Nashville Public Schools built a solid SEL foundation by participating in the Collaborating Districts Initiative which they joined in 2013. However, data gained through SEL classroom walkthroughs in combination with other school climate indicators (e.g., discipline data) continued to show that students of color were being disproportionately suspended and expelled. This data, coupled with a rise in community violence, compelled the district to focus on becoming more trauma-informed within the last 5 years. In 2016, the district established the district trauma-informed schools initiative. The central office deployed a trauma-informed schools team to begin widespread training on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and TIP, serving 15,000 faculty and staff and 5,000 stakeholders through a train-the-trainer model. A mix of partnerships plus state and local funding supported this work.

More recently, the district rolled out a proactive approach using Advocacy Centers to integrate SEL and TIP at all 72 elementary schools. An Advocacy Center is a space in the building where students are directed to before a disciplinary strategy is implemented. Each center is staffed by a full-time person to address any underlying social or emotional needs of students who enter the space. Staff provide short-term (15- to 30-minute) interventions for students such as breath work or movement/yoga, reflective dialogue, and connection with a caring adult. This allows the student time, space, and support to de-escalate. If a disciplinary response is still needed, the district expects staff to engage in restorative practices. By promoting healing-centered engagement over punitive discipline, the district models another key principle related to SEL and trauma sensitivity.

The Metro Nashville trauma-informed schools team continues to provide consultation, resources, and other supports to schools districtwide—including individualized student supports, student voice sessions, and adult wellness sessions—with an overarching commitment to combatting racism and oppression in all forms.

Conclusion

These three districts described wide variability in their implementation strategies. Their starting points differed, as did the sociopolitical landscape within which each is situated. However, all three districts focused first on taking care of the adults who support students and families. By focusing on the adults first, we can begin to heal from the challenges of the past two years.

Additional lessons learned from the three districts are summarized in this companion blog post from Region 9: “How can social and emotional learning (SEL) and trauma-informed practices (TIP) help us right now?” written to capture the three main lessons-learned from the panel.

Thank you to Chelsea Montgomery, Maressa Jensen, Ted Wilson, and Mary Crnobori for sharing their district SEL and TIP journeys. We wish you continued success and endurance as you continue to support the adults, students, families, and communities of Fulton County, Juneau, and Metro Nashville. Special thank you to Nanmathi Manian from the National Comprehensive Center for her support.

Resources

The following three briefs informed this session:

- Becoming Trauma Informed: Taking the First Step to Becoming A Trauma-Informed School

- Trauma-Sensitive Schools and Social and Emotional Learning: An Integration

- Implementing Trauma-Informed Practices in Rural Schools

Mara Schanfield leads the Region 9 Comprehensive Center’s teacher retention project with Chicago Public Schools and is a senior technical assistance consultant at the American Institutes for Research. Schanfield, a licensed school counselor, has more than 15 years of experience supporting students, educators, and social and emotional learning in school and out-of-school time settings.