By Daniel M. Frederking, EdD, and Dee Ann Schnautz, PhD

September 7, 2021

Teachers depend on academic data for all sorts of important tasks, ranging from determining instructional start points and identifying struggling learners to dividing the class into smaller groups for tailored instruction. But the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic mean that the information on which they relied in the past may not be available or trustworthy. As we kick off this unique 2021–22 school year, many educators are struggling with what data to use and how to do so responsibly. So, as a school leader, how can you help your teachers? One idea is to bring formative data to the forefront of your comprehensive balanced assessment system.

What Data Are Teachers Missing?

If your teachers normally rely on standardized reports from a local benchmark assessment or the state assessment, they might be running into some problems lately. Those reports might not exist (because the test was never given), or their accuracy might be questionable (for many pandemic-related reasons). To some, this lack of data might not be viewed as a big loss. To schools that constantly use these reports when making decisions, it can have a big impact.

In many cases, this situation means teachers will lose norm-referenced data that compare students’ performance to that of their peers, often displayed through percentile rankings. This type of data is in contrast to criterion-referenced data, which compare students’ performance directly to a set of standards or objectives. In these situations, we often use terms like mastery or performance levels to show student learning in comparison to what the objectives say students should be able to do.

If the normal standardized data aren’t available, it might be necessary to shift the focus more heavily on criterion-referenced data. This shift in focus isn’t a bad thing at all; it’s just an adjustment that might take a little getting used to. And you might find that you already have the right systems in place.

The Strengths of a Comprehensive Balanced Assessment System

More than ever, it is time to emphasize the power of a comprehensive balanced assessment system. A system like this frames data collection around three forms of assessment:

- Formative

- Interim

- Summative

Each of these forms of assessment is used for specific purposes, and each obviously has been affected by the pandemic. But one of the strengths of this system is the ability to fall back on one type of assessment when another one fails.

If your local benchmark (interim) assessment is faulty or not available, this might be an opportunity to bring the formative assessments to the forefront. Ever since Black and Wiliam’s landmark 1998 study, which showed the value of formative assessment to evaluate student learning, teachers have been made very aware of the different types of assessment within their preparation programs. As research has continued to show the benefits of formative assessment (Black & Wiliam, 2009; Bennett, 2011; Ozan & Kincal, 2018), informal checks of student understanding may be commonplace in many classrooms. One weak spot, though, is keeping all that information straight. Helping educators set up a system for tracking these data could boost their ability to use the data to guide instruction and check for mastery.

One Simple Strategy: Formative Reports

One advantage that formative checks have over interim assessments is that teachers can use the data in real time. This ability contributes to the teachers’ and students’ capacity to continuously inform the learning process with data. The interim assessments are useful, but they can’t be applied simultaneously with the instruction.

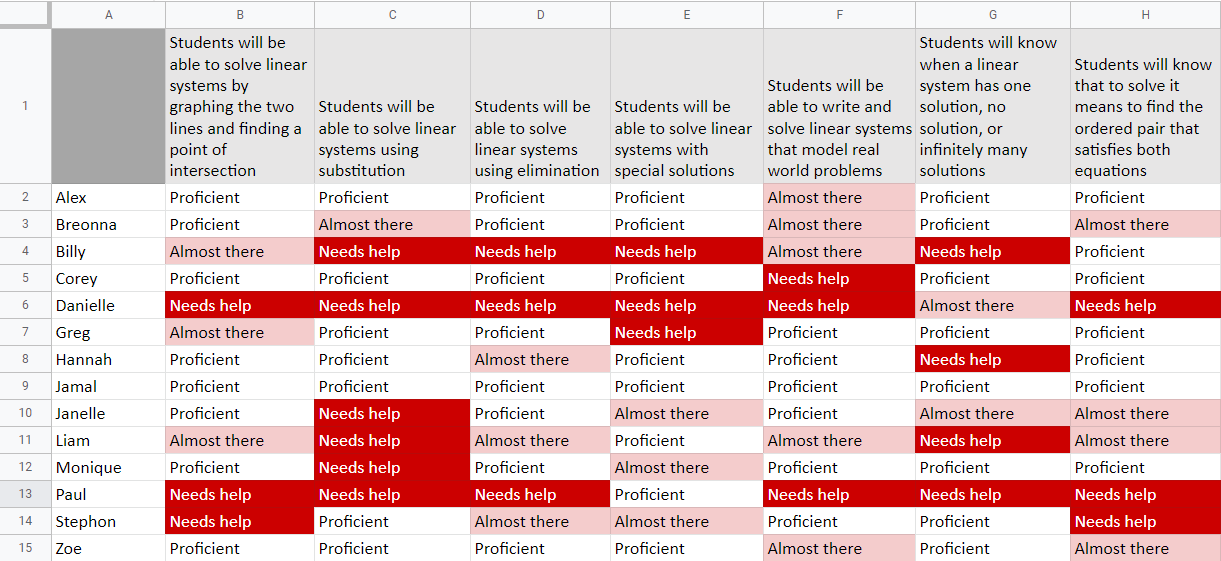

Take the example in the image below. Using a simple spreadsheet, teachers can produce a resource that provides at-a-glance information that’s likely not available anywhere else, aside from in their own head. The column headers across the top list the objectives that are being covered during the unit at hand, and each row represents a student in the class. Using a simple system of three levels (Proficient, Almost there, and Needs help), the teacher can informally capture their own formative assessment of the level of each student’s learning.

This evidence-based strategy [PDF] does not require a formal assessment. It can be as simple as walking around the room and observing the students. On any given day, as students work on their lesson, the teacher might decide to gauge each student’s progress on an objective. The teacher walks around with a notepad and marks down one of the three levels for each student. After multiple rounds of observing and marking down levels, the teacher has a criterion-referenced report that can provide valuable assistance in decision making.

A tool like this could take on any form that’s most effective for the teacher: a spreadsheet, a hand-drawn table, etc. The usefulness of this resource can be observed immediately. Teachers can apply it to instructional grouping, decisions on reteaching, and individual interventions. Even though it is an informal assessment method, this pseudo-standardized approach can fill in the gap caused by missing or inaccurate data.

The Power of Data

A comprehensive balanced assessment system is an important strategy in monitoring a student’s progress every step of the way. Triangulating your data using a variety of sources provides a more accurate picture of student achievement. The unsung advantage to a system like this is that when one data source fails, there are still other sources on which to fall back.

As you prepare for this school year, consider the ways that teachers can leverage other sources of assessment data to meet students where they are. If you find that you have a hole in your data, pivot your focus to other assessment forms. This might take some collaboration time and professional development, but it can have an immediate impact on student outcomes. Every school works within its own context, so be sure to consider the needs of your staff and students when developing a plan. What works for one might not work for all. But the important thing to remember is the power that lies within a data-driven teaching and learning system.

References

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 7–74.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(5).

Bennett, R. E. (2011). Formative assessment: a critical review. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 18(1), 5–25.

Ozan, C. & Kincal, R. Y. (2018). The effects of formative assessment on academic achievement, attitudes toward the lesson, and self-regulation skills. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 18(1), 85–118.

About the Authors

Daniel M. Frederking, EdD, is a senior technical assistance consultant with the American Institutes for Research, a position he has held for 5 years. In this role, he works closely with districts, schools, universities, and state education departments in building a more data-literate workforce. He previously served as a principal consultant for the Illinois State Board of Education and as a high school language arts teacher.

Dee Ann Schnautz, PhD, is an assistant professor of practice for the Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, College of Education. She serves on the executive committee of the Illinois Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. She previously served as a district office director of curriculum, instruction, and assessments; an elementary school principal; a middle school assistant principal; and a middle school and an elementary classroom teacher.

Photo by Allison Shelley for EDUimages.