Recruiting and retaining teachers of color has long been an unrealized policy goal. In 1998, then–U.S. Education Secretary Richard Riley said, “Our teachers should look like America.” Despite persistent racial disparities between teachers and students and inconsistent support for practices, policies, or research to support diversifying the educator workforce, the tide may be beginning to turn.

Earlier this year, the U.S Department of Education and current Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona emphasized supporting a diverse educator workforce and professional growth to strengthen student learning. This vision offers a new pathway for supporting and elevating the teaching profession while supporting diversity.

Secretary Miguel Cardona has called upon schools, school districts, postsecondary education officials, and state education agencies to address four priority areas to support students, educators, and school communities as they continue to correct inequities that have long existed in our education system to ensure all students can both succeed and thrive:

- Support students through pandemic response and recovery.

- Boldly address opportunity and achievement gaps.

- Make higher education more inclusive and affordable.

- Ensure pathways through higher education lead to successful careers (U.S. Department of Education, 2022).

The Region 9 Comprehensive Center partnered with its Advisory Board to establish the Diversifying the Teacher Workforce affinity group, a community of diverse teachers and leaders with a shared interest in exploring and applying evidence-based practices for recruiting and retaining teachers of color. In response to Secretary Cardona’s call to address education inequities, the Region 9 Comprehensive Center used a mixed-methods approach, which included examining national and state demographic data, conducting policy scans, and conducting five, hour-long interviews with Advisory Board members to provide insights and strategies for supporting a diverse teacher workforce to strengthen student learning in schools and districts in Illinois, Iowa, and nationwide that align with the Secretary’s four priority areas.

Support students through pandemic response and recovery: Why should schools and school districts address the cultural and/or ethnic mismatch between students and teachers?

The COVID-19 pandemic and growing awareness of widespread social inequities, often referred to as the twin or double pandemics (Shim & Starks, 2021), have led to growing calls to recruit, retain, and train a diverse educator workforce (Carver-Thomas, 2018; Carver-Thomas et al., 2021; Goe & Roth, 2019). School districts and education systems nationwide and across the states served by the Region 9 Comprehensive Center have seen an increase in student diversity, though efforts to hire and retain diverse professional school staff have not kept pace with student demographic changes.

Evidence shows that establishing a diverse workforce is associated positively with the closure of student academic and opportunity gaps such as increased standardized test scores, improved attendance, lower attrition rates, higher enrollment in advanced-level courses, raised graduation rates, and increased college enrollment rates for historically excluded students (Villegas & Davis, 2008; Villegas & Irvine, 2010). In addition, a 2017 study published by the Institute of Labor Economics revealed Black students in grades 3–5 who also were low income were more than 30 percent less likely to drop out of school and had increased college aspirations if they were paired with at least one Black teacher during their education careers (Perry, 2017).

Moreover, having a diverse educator workforce supports student social and emotional wellness and development, as students have opportunities to see diverse teachers as “strong counter-stereotype models” that counter negative images or stereotypes of people of color (Sleeter & Zavala, 2021, p. 228). Unfortunately, while data points to beneficial outcomes for students when the educator workforce is diverse, current teacher demographic trends have yet to reflect the student population.

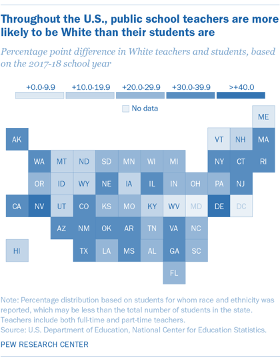

A report on teacher and student diversity across the country by the Pew Research Center found that eight of 10 public schools in the United States reported having a teaching staff that is almost 80 percent White, with 47 percent of students being White, during the 2017/18 school year (Schaeffer, 2021).

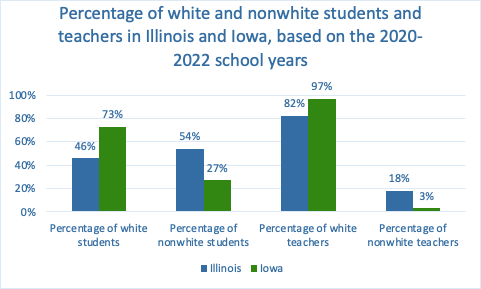

According to data from the Illinois State Board of Education 2020/21 Illinois Report Card, 82 percent of teachers in the state were White, compared to 46 percent of the student population (Illinois State Board of Education, 2021).

Moreover, although 27 percent of students enrolled in Iowa K-12 public schools identify as nonwhite, demographic data from the Iowa Department of Education show that during the 2021/22 academic year, only 2.7 percent of teachers in the state were of color (Iowa Department of Education, 2022).

These statewide percentages indicate that while existing district and state efforts to recruit and retain teachers have been successful in attracting white teachers, there are opportunities to grow and develop a diverse educator workforce that reflects student demographics. With teacher shortage areas in Iowa impacting multiple content areas including mathematics, ELA, and science and unfilled positions in Illinois totaling over 5,000, successfully hiring and retaining underrecruited teachers of color could address teacher shortages while improving students’ learning experiences throughout the region and across the country.

Boldly address opportunity gaps: How can professional development opportunities close gaps through recruiting and retaining a diverse educator workforce?

Cardona’s call to boldly address opportunity gaps challenges states and districts to fix broken systems that may perpetuate inequities in our school through investing in, recruiting, and supporting professional development initiatives so people from all backgrounds can participate in the educator workforce. For example, recruiting outside the “traditional” educator pipeline to include hiring and promotion opportunities for special education teachers, paraprofessionals, and bilingual educators can broaden the pool of diverse applicants.

“So, I arrived [at my district] in July 2020, and once I found out that we were not recruiting at HBCUs, I said, well, we can start there.”

— Dr. Teresa Lance Assistant Superintendent for Equity and Innovation, School District U-46 (Elgin, Illinois)

Partner with Historically Black Colleges and Universities. School districts may consider developing relationships with Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) to create diverse pipeline partnerships. In 2014, HBCUs conferred 16 percent of degrees in education, with Black students accounting for more than a third of education graduates across the nation (Perry, 2017). The educator pipeline often looks to local and regional networks to fill job openings, leaving HBCU networks unexplored.

As schools and districts shift recruitment efforts to include HBCUs and other diverse postsecondary institutions, asset-driven mindsets can expand regarding such institutions as effective partners in providing high-quality teachers from historically excluded backgrounds; this could both strengthen and diversify the educator pipeline (Motamedi & Stevens, 2018; Perry, 2017). Combining grow-your-own efforts alongside forming partnerships with HBCUs can be an effective approach to diversifying the educator workforce. There are more than 100 HBCUs across the United States, with more than 220,000 students. As of the 2021/22 academic year, 79 HBCUs offered education programs in 19 states and the District of Columbia.

“I think when we can treat teaching like perhaps a medical residency that we then could remove a potential barrier for some people entering the field”.

— Dana Schon Profession Learning Director, School Administrators of Iowa

Explore strategies from other fields. The medical field has been introducing financial incentives that reflect students’ economic circumstances to recruit and retain candidates. For instance, in 2018, the School of Medicine at New York University (NYU) waived its tuition to both alleviate the strain of financing a medical degree, which can cost upwards of $200,000, and attract diverse applicants. Since the policy was implemented, total applications have increased by 47%, and applications from underrepresented groups have more than doubled. Moreover, applications by students who identify as Black have risen by 142%.

In addition, fields ranging from geography to sociology use a recruitment technique to diversify candidate pools called snowball sampling, a method in which recruiters ask current team members to explore their social networks to identify potential candidates. For underrepresented groups, relationship-based recruitment strategies like snowballing have been more effective than more traditional recruiting practices because they rely on the trust and cultural competence of people within a community to make connections, thus personalizing the approach for candidates who may be interested in future or current positions (Sadler et al., 2010).

Hire in cohorts. Schools and districts can set hiring policies and practices that recruit two or more teachers of color into each entering cohort to help create an intra-departmental network of support for teachers of color. Communicating clear hiring policies and practices is a sustainable method for demonstrating to potential candidates that the school or district values transparency and has goals for diversity the educator workforce beyond hiring one or two teachers of color (Virginia Commonwealth University, n.d.).

Offer strong mentoring. Research shows that teachers of color often face structural, interpersonal, and pedagogical constraints within the profession, which can affect relationship building and professional development (Pour-Khorshid, 2018). Moreover, that same research also found that receiving quality mentoring, especially when mentors are also educators of color, also helps to mitigate the stressors associated with the barriers in the profession (Pour-Khorshid, 2018).

Developing strong mentoring relationships can create opportunities for teachers of color to create trusting relationships within the school system, which can support professional development and growth within the school and district. Provision of opportunities for teachers of color to work collaboratively with colleagues can mitigate feelings of isolation and help these educators grow professionally. Although formal mentoring relationships benefit relationship and professional development, more informal connections also may provide trusted relationships and spaces that support educators of color. Research suggests successful mentor selection includes recognizing “the organizational conditions of the school, the strength of the school’s leadership team, and overall fit, as well as how assignments are aligned with new hires’ content expertise” (Kimmel et al., 2021; Motamedi & Stevens, 2018, p. 5).

“Once we get African American teachers, or teachers of color, what are we doing to make them feel as though they belong, that they are valued, and we weren’t paying attention to that. So what has changed [to reduce isolation and build a more inclusive environment] is, we have five affinity groups that we started last year: African American, Asian American, Latinx, LGBTQIA, and white allyship.”

— Dr. Teresa Lance Assistant Superintendent for Equity and Innovation, School District U-46 (Elgin, Illinois)

Provide diverse spaces like affinity groups. Affinity groups are defined as “groups of employees within an organization who share a common identity, defined by race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, disability, or shared extra-organizational values or interests” (Briscoe & Safford, 2010, p. 42). Teachers of color may experience workplace well-being challenges, such as loneliness and isolation; racial animus from colleagues and administrators; and unbalanced or biased school policies, systems, and practices. Affinity groups can alleviate these issues by providing support and spaces to address specific challenges for educators of color (Great Schools Partnership, 2021).

Since educators of color may find themselves isolated from one another within school districts, affinity groups provide an opportunity to work across the system rather than strictly within it. Affinity groups create a safe space for people with something in common to come together and find connection, support, and inspiration. Such groups also can facilitate sharing of useful information, such as local beauty and/or barber shops, restaurants, and other local venues and activities that help make living and working away from familiar surroundings more comfortable.

School and district leaders have begun to provide diverse spaces for educators. Within the Region 9 Comprehensive Center, Illinois schools are recruiting affinity group facilitators to cultivate authentic, inclusive, and intersectional spaces to support educators of color. The Teach Plus training program trains leaders to identify barriers to retention of educators of color and propose and advocate for solutions. The program operates groups across six Illinois regions, building the capacity for education leaders to facilitate affinity groups in their site-specific contexts (Teach Plus, 2022).

Make higher education more inclusive and affordable: How can states build a more affordable and inclusive education system that supports graduates from teacher preparation programs?

Affordability and inclusivity gaps in higher education remain systemic barriers that prospective educators of color may also face as candidates entering the teacher workforce. States have implemented promising programs and policies to support teacher candidates once they leave higher education by closing equity and opportunity gaps in teacher recruitment and retention.

The Florida Critical Teacher Shortage Program found that its loan forgiveness program for early career teachers had a positive effect on teacher retention. The study also found that a one-time retention bonus of $1,200 offered to high school teachers in designated subject areas decreased teacher attrition in targeted areas by as much as 25 percent (Feng & Sass, 2015).

In addition, Tennessee has implemented a three-year “earn and learn” teacher apprenticeship program that enables teachers to earn wages rather than pay for training to address shortages, providing access to education, training, and workforce opportunities for diverse candidates that may have been otherwise unaffordable.

Costly teacher licensure exams (e.g., PRAXIS) can disproportionately create barriers for teacher candidates of color despite little evidence that these exams predict teacher effectiveness (Goldhaber & Hansen, 2010; Petchauer, 2012). States across the country and within the Region 9 Comprehensive Center have updated teacher licensure policies to remove this barrier.

In May 2022, Colorado passed House Bill 1220, “Removing Barriers to Educator Preparation.” The bill creates additional pathways aside from the PRAXIS to obtain teacher licensure and provides stipends to eligible student teachers during their residency (Dugan, 2022). One month later, Louisiana passed House Bill 546, which allows entry into teacher preparation programs without taking the PRAXIS. Additionally, the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction and the Mississippi Department of Education have recognized licensure exams as exclusionary practices and have developed alternative or performance-based programs to offer a variety of pathways toward licensure (Lachlan-Haché et al., 2020).

Within the Region 9 Comprehensive Center, Iowa eliminated the requirement that graduates from its teacher preparation programs had to pass a program completion assessment to be eligible to receive a teaching license in June 2022 (Iowa Board of Educational Examiners, 2022).

Ensure pathways through higher education lead to successful careers: When should talent development begin?

“We have to make access into our profession equitable for all kids, we have to do a better job of promoting our profession in all communities.”

— Lindsey Jensen 2018 Illinois Teacher of the Year and Early Career Development Director, Illinois Education Association

Cardona’s vision for American education calls for cross-collaboration among organizations and groups to invest in career preparation programs that meet the needs of today's economy so that students are prepared for today and for the future. Initiatives such as investing in colleges and universities that serve underrepresented groups, increasing access to and funding for students who need it (e.g., Pell Grants), and prioritizing grant programs that allow students to return to higher education or pursue career and technical education programs at any point in their lives and careers can develop and strengthen a diverse educator workforce.

“I think things like signing days for those choosing education can be one way that we [shift the narrative around public education]”.

— Dana Schon Professional Learning Director, School Administrators of Iowa

Career and technical education (CTE) programs can be designed and implemented to establish the connection between what P–12 students are learning in the classroom and how it can be applied to postsecondary education and the workforce. Programs like Educators Rising build networks with educators, colleges, and other partners to establish pathways and opportunities for building a diverse teacher workforce by providing Grow Your Own programming and student activities based on their interests and needs. The program also works with CTE students in grades 6–12 as they learn about the teaching profession and curriculum and instruction pedagogies to prepare for both postsecondary education and the teacher workforce.

Other programs, such as Teachers of Tomorrow at the University of Delaware, offer targeted supports to students entering grades 11 and 12 from underrepresented and historically excluded backgrounds who are interested in teaching as a career. The program first provides a free, 2-week summer institute at the University of Delaware, and once enrolled, students receive resources, coaching, and mentorship through the college application process and throughout their time at the University. The goal of the program is to remove barriers and prepare the next generation of teachers with hands-on academics and opportunities to learn more about the field (College of Education & Human Development, University of Delaware, 2020).

References

Biscoe, F., & Safford, S. (2010). Employee affinity groups: Their evolution from social movements vehicle to employer strategies. Perspectives on Work, 14(1), 42–45. http://www.personal.psu.edu/fsb10/paper_other/Briscoe%20Safford%20Employee%20Affinity%20Groups%20POW%202010.pdf

Carver-Thomas, D. (2018). Diversifying the teaching profession: How to recruit and retain teachers of color. Learning Policy Institute. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED606434

Carver-Thomas, D., Leung, M., & Burns, D. (2021). California teachers and COVID-19: How the pandemic is impacting the teacher workforce. Learning Policy Institute. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED614374.pdf

College of Education & Human Development, University of Delaware (2020, April 9). UD’s teacher pipeline program prepares high school students for careers in education [Blog post]. https://www.cehd.udel.edu/teachers-of-tomorrow/

Dugan, S. (2022, May 31). Law signed by governor pays eligible students for teacher training and removes standardized test barrier for teacher qualification. CU Denver News. https://news.ucdenver.edu/law-signed-by-governor-pays-eligible-students-for-teacher-training-and-removes-standardized-test-barrier-for-teacher-qualification/

Goe, L., & Roth, A. (2019). Strategies for supporting educator preparation programs’ efforts to attract, admit, support, and graduate teacher candidates from underrepresented groups (Research Memorandum No. RM-19-03). Educational Testing Service.

Goldhaber, D., & Hansen, M. (2010). Race, gender, and teacher testing: How informative a tool is teacher licensure testing? American Educational Research Journal, 47(1), 218–251. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831209348970

Great Schools Partnership. (2021). Racial affinity groups: Guide for school leaders. https://www.greatschoolspartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Racial-Affinity-Groups-Guide-for-School-Leaders-Final.pdf

Illinois Department of Education. (2021). Illinois report card: State snapshot. https://www.illinoisreportcard.com/State.aspx

Iowa Department of Education. (2022). Iowa achievement gaps legislative report. 2022-06-09 Closing the Achievement Gaps Report 2022 | Iowa Department of Education (educateiowa.gov)

Iowa Board of Educational Examiners. (2022). https://boee.iowa.gov/

Kimmel, L., Lachlan, L., & Guiden, A. (2021). The power of teacher diversity: Fostering inclusive conversations through mentoring. Region 8 Comprehensive Center. https://region8cc.org/sites/default/files/reg-8-resource-files/30190_R8CC_OH_Power_of_Teacher_Diversity_v9_RELEASE_508.pdf

Lachlan-Haché, L., Causey-Konaté, T., Kimmel, L., & Mizrav, E. (2020). To achieve equity, build a diverse workforce. Learning Professional, 41(6). https://learningforward.org/journal/building-the-pipeline/to-achieve-equity-build-a-diverse-workforce/

Motamedi, J. G., & Stevens, D. (2018). Human resources practices for recruiting, selecting, and retaining teachers of color. Regional Educational Laboratory Northwest. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/northwest/pdf/human-resources-practices.pdf

Perry, A. (2017, May 16). "Discovering" black teachers at HBCUs. Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/discovering-black-teachers-hbcus/

Petchauer, E. (2012). Teacher licensure exams and Black teacher candidates: Toward new theory and promising practice. Journal of Negro Education, 81(3), 252–267.

Pour-Khorshid, F. (2018). Cultivating sacred spaces: a racial affinity group approach to support critical educators of color. Teaching Education, 29(4), 318–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2018.1512092

Sadler, G. R., Lee, H.-C., Lim, R. S.-H., & Fullerton, J. (2010). Recruitment of hard-to-reach population subgroups via adaptations of the snowball sampling strategy. Nursing and Health Sciences, 12(3), 369–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00541.x

Schaeffer, K. (2021). America’s public school teachers are far less racially and ethnically diverse than their students. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/12/10/americas-public-school-teachers-are-far-less-racially-and-ethnically-diverse-than-their-students/

Shim, R. S., & Starks, S. M. (2021). COVID-19, structural racism, and mental health inequities: Policy implications for an emerging syndemic. Psychiatric Services, 72(10), 1193–1198. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000725

Sleeter, C. E., & Zavala, M. (2021). What the research says about ethnic studies. National Education Association. https://www.nea.org/sites/default/files/2020-10/What%20the%20Research%20Says%20About%20Ethnic%20Studies.pdf

Teach Plus. (2022). How we grow teacher leaders. https://teachplus.org/what-we-do/how-we-grow-teacher-leaders/

U.S. Department of Education. (2022, January 27). Secretary Cardona lays out vision for education in America [Press release]. https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/secretary-cardona-lays-out-vision-education-america

Villegas, A. M., & Davis, D. (2008). Preparing teachers of color to confront racial/ethnic disparities in educational outcomes. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, & J. McIntyre (Eds.), Handbook of research in teacher education: Enduring issues in changing contexts (pp. 583—605).

Villegas, A. M., & Irvine, J. J. (2010). Diversifying the teaching force: An examination of major arguments. The Urban Review, 42, 175—192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-010-0150-1

Virginia Commonwealth University. (n.d.). Strategies for successfully recruiting a diverse faculty. https://www.ccas.net/files/ADVANCE/VCU%20Expand%20the%20Pool.pdf